That’s Not All Right, Mama.

‘“Down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now and I said if I ever got to the place where I could feel what old Arthur felt, I’d be a music man like nobody ever saw.”

Elvis Presley

Tom McGuinness, (left) a British blues pioneer, ex-member of the chart topping 60s favourites Manfred Mann, returned to his first love, the blues, in 1979 as a founder member, with Paul Jones, of the UK’s premier R&B group, The Blues Band, currently celebrating their 35th anniversary.

Tom once told me a story which haunted me for years. Not long before he died, in the early 1970s, legendary bluesman Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup came over to Britain from the US to play in one of the highly successful American Folk Blues festivals which had been running as popular events since the mid-1960s.

As Crudup had nowhere to stay, Tom invited him to bed down at his flat in London. What struck him immediately was how poverty-stricken the great man seemed to be. After all, Crudup had written three of Elvis’s biggest hits – including his first multi-million selling single on Sun Records, That’s All Right, Mama. Many had already dubbed him ‘the Father of rock’n’roll.’ Yet he didn’t even have a decent guitar, was poorly dressed, and when he took his stage suit out of his battered old suitcase at Tom’s place, he discovered that the rats back home had eaten the back out of his jacket. McGuinness had to find him some new threads to wear to perform in. Tom had the privilege in 1970 of recording The London Sessions with Crudup, along with Benny Gallagher and Hughie Flint.

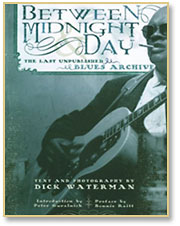

Big Boy Crudup’s is perhaps the cruellest and most poignant story concerning non-payment of royalties. In his wonderful book, Between Midnight and Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archive ,photographer, writer, blues manager and promoter Dick Waterman outlines his battle for Crudup’s royalties with a sensitivity which can literally move a reader to tears.

Arthur was born in Forest, Mississippi, on August 24th 1905, and died on 28 March 1974, in Nassawadox, Virginia. Six foot four inches tall, he was no stranger to hard, physical labour, and for most of his life worked in various rural jobs. Unlike many of his musical peers, he was a late-comer to learning the guitar, which he didn’t pick up until he was 32. His guitar playing mentor was a local blues player known as Papa Harvey. Arthur never became what we’d call a virtuoso on the instrument, but his spirited and rhythmic accompaniment, along with his high, clear voice soon got him noticed. After an early spell in Clarksdale, Mississippi, playing at blues parties, like many other men in the region, in search of a better living he headed north to Chicago, where he played on street corners. At first, the windy city didn’t provide him with the income he’d hoped for, and he ended up living in a packing crate underneath Chicago’s elevated railroad.

The story goes that he was playing for loose change on the sidewalk when he was discovered by Chicago’s legendary blues ‘Mr. Fixit’, Lester Melrose. Melrose had moved to Chicago around 1914, and hoped to find success as a catcher for the Chicago White Sox baseball team, but his trial failed. He became a grocery salesman. Around 1920, together with older brother Walter and Marty Bloom, he established The Melrose Brothers Music Company, a publishing house and music store on Chicago’s south side. It was in his shop that he met Jelly Roll Morton (1885-1941) who would become Melrose’s chief writer and arranger. By 1925 Lester had found his metier – as a record producer and, most importantly, a talent scout. He sold his share in the shop and began promoting the best of the many blues artists who were arriving in Chicago, and his aptitude paid off handsomely with the recording of It's Tight Like That with Tampa Red (1904 -1981, a.k.a. Hudson Woodbridge and Hudson Whittaker), an influential guitarist and singer from Georgia. Of course, as a publisher, Melrose was as wily as the rest, and knew the value of taking possession of his artists’ compositions.

Crudup landed a significant gig to play at Tampa Red’s house. His playing went down well enough to get him signed, through Melrose, to RCA/Bluebird Records, who released his first recording, If I Get Lucky. Over the years he would cut dozens of tracks for Vocalion and Bluebird, tour with Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller) and Elmore James, among others, with most of his songs, in particular, Mean Old Frisco establishing him as a major figure on the blues scene. Yet the non-payment of royalties led him to fall out with Lester Melrose. In a 1973 documentary , Crudup said

“Every time I’d go make a record, I’d ask Lester, ‘How many records would a man have to make that he didn’t have to work on the farm?’ I could hear my songs on the jukebox all through the South. I had a disc jockey tell me, ‘Now, Arthur, you’re supposed to be in good shape. Your records are selling second from the top. I never knew how much progress I was makin’ because Melrose didn’t tell me. ”

Eventually, sick of the music business, he headed down to Mississippi where for a while he ran a bootleg liquor operation, an enterprise which equally matched his skill as a musician, as, apparently, folks came from far and wide for Big Boy’s moonshine. Yet whilst he was making a few bucks distilling Virginia’s finest, his compositions, such as That’s All Right, Mama, My Baby Left Me and So Glad You’re Mine would all be recorded by Elvis Presley and legally this should have made him a rich man. Yet that was not to be. He would die virtually penniless.

|

| Elvis owed Big Boy Crudup a few dollars (or at least Tom Parker, his manager did) |

In 1968 Dick Waterman, a truly great photographer, superb chronicler of the blues and manager of stars such as Buddy Guy, Big Mama Thornton and Bonnie Raitt, was Crudup’s booking agent during the late 1960s blues revival. He asked Crudup if he’d received any royalties. He had; a few sporadic cheques for nine, twelve and eighteen dollars. Unfortunately, on April 12 that year, Lester Melrose had passed away in his sumptuous villa down in Florida, aged 74, owning the rights to over 3,000 songs, none of which he had written. Waterman enrolled Big Boy Crudup in AGAC, the American Guild

of Authors and Composers, and the fight for Arthur’s royalties began.

A large firm, Hill and Range, had taken over the affairs of Lester Melrose. After nearly five years of legal wrangling, AGAC informed Waterman that they had come to a settlement with Hill and Range. Waterman agreed to meet Crudup in New York at Hill and Range’s office. With his daughter and three sons, the old man had driven all the way up from Virginia, where he’d spent his later years as a farm labourer.

|

| Dick Waterman, (left) and another great fighter for missing royalties, Bonnie Raitt. |

That arrival in a cold New York had promised to be an exciting day, as the cheque Arthur expected to take home with him was for $60,000. They went into Hill and Range’s offices and the lawyer asked them to wait whilst he went upstairs to the President’s suite to get the cheque. It was a long wait. Yet when the lawyer returned, he was not bearing money – just bad news. The company wouldn’t sign the agreement, saying “It gives away more in settlement than you could hope to get through litigation.” Waterman describes the tragic scene; “Arthur looked at me and I said, ‘They’re not going to pay you, Arthur. You’re going to have to sue them. We’re going to have sue Lester Melrose’s widow.’ But the idea of a black man suing an elderly white woman—it just wasn’t gonna happen.”

The message was cruel and clear – yes, we owe you – yet you’re an old black guy and if you want your money, you’ll have to see us in court. The prospect of pursuing Rose, the surviving widow of Lester Melrose was hopeless. With great dignity Crudup thanked Waterman for all his efforts, saying

“I know you done the best that you could. I respects you and I honours you in my heart. Them people got their ways of keeping folks like me from getting any money. Naked I come into this world and naked I shall leave it. It just ain’t meant to be.”

Compared to Virginia, it was decidedly wintry in New York and both Arthur and his family weren’t dressed for the weather. Shivering, they turned towards their old car, his sad parting shot being

“I ’spect we better start driving now. We got a ways to go.”

A poor man, he died shortly after, on March 28, 1974. But Dick Waterman hadn’t finished. Disgusted, on his way home from Crudup’s funeral, he had a meeting with another lawyer, Ina Meibach, in New York City. Meibach acted to stem the flow of any record company royalty payments to Hill and Range. At that time Chappell Music was in the process of buying out Hill and Range and Dick’s action on behalf of the late Arthur Crudup showed up on Chappell’s corporate radar as the very thing in the take-over package they didn’t want to buy – a legal dispute over an artist’s estate. That would have generated some unpleasant publicity. As Dick said,

“We had the leverage that we needed”.

The first cheque Arthur’s family received was for $248,000 dollars, and since then they’ve had over $3 million more.

One might imagine that there’d be some kind of marker or plaque alongside Virginia’s Route 13 noting that the “Father of Rock ’n’ Roll,” the legend who gave Elvis his first-ever hit and whose work was covered by everyone from Eric Clapton to Creedence Clearwater Revival and Elton John lived and died here. As Dick Waterman commented, “There probably wasn’t a week during the decade of the 1970s when there wasn’t an Arthur Crudup song on the Billboard Top 200 albums,” he says, rambling off a list of seminal rock albums from Clapton’s Slow Hand (“Mean Old Frisco”) to Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Cosmo’s Factory (“My Baby Left Me.”) As well as the likes of Elvis and Clapton, he wrote numerous other blues classics for artists such as B. B. King, Big Mama Thornton and Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland.

His grave in Franktown, Virginia had to wait until 25 years after his death - the 1990s – before it even had a headstone. Stories about royalty rip-offs occur throughout the music business, but some of the downright chicanery pulled off back in the bad old days has been put to rest. Over the last decades of the 20th century musicians have become more shrewd. They’ve no doubt taken the astute advice of Willie Nelson, who famously gave away the rights of one of his first, and most famous, songs Family Bible for a pittance;

“What I’m saying to all you songwriters is to get yourself a good Jewish lawyer before you sign anything, no matter how much (the publishing or) record companies say they love you. ”

You can read a lot more about royalty rip-offs, racism,dodgy managers and other tragedies in my book Good Time Charleys: Tough Tales fromRhythm & Blues. e-mail me at roybainton@hotmail.com for details

You can read a lot more about royalty rip-offs, racism,dodgy managers and other tragedies in my book Good Time Charleys: Tough Tales fromRhythm & Blues. e-mail me at roybainton@hotmail.com for details