Charles Hoy Fort (1874-1932) was an American writer and researcher

into anomalous phenomena. Today, the terms Fortean and Forteana

are used to characterize various such phenomena.

Fort's books sold well and are still in print today.

I first began reading Fort's works 50 years ago,

and one Victorian story collected by Fort,

which came from a curious report in the London Times,

has always haunted me.

The following yarn is my fictional take on that peculiar event.

into anomalous phenomena. Today, the terms Fortean and Forteana

are used to characterize various such phenomena.

Fort's books sold well and are still in print today.

I first began reading Fort's works 50 years ago,

and one Victorian story collected by Fort,

which came from a curious report in the London Times,

has always haunted me.

The following yarn is my fictional take on that peculiar event.

Out of the Marvellous

The chess-board is the world,

the pieces are the phenomena of the universe,

the rules of the game are what we call the laws of Nature.

The player on the other side is hidden from us.

Thomas Huxley,

English Biologist (1825-1925)

Dark and ragged like the damaged wings of a savaged bird stood the forlorn branches of the trees, frozen in misery against the oppressive low grey fog of the stooping sky.

In the Year of Our Lord 1853 this was not the day of absolute bliss they had in mind. Long had the bride and groom dreamt of their act of union, envisioning it beneath the chirp of spring’s arriving birds, perhaps wheatears or chiffchaffs, hovering over them in an azure firmament. Yet there were no avian guests. That the Gods had decided different could only be an ominous disappointment. It seemed as if the sun itself, like a spent candle, had spluttered out and died. Even the grass of the graveyard appeared to have forgotten its duty to be green, opting this day for a strange shade of murky khaki. Only the medieval stonework of the tiny church was true unto itself, its ancient green and mustard freckled moss crawling across the rugged slabs, obliterating the marks of long-dead masons.

The air around the church was heavy, a perverse, crushing weight of humidity, not of a tropical nature, but a dense, cold clamour which stroked humanity with pitiless dead fingers. It seemed to make even breathing difficult, as if some foul, silent consumptive wall of wet air had insinuated itself into every present pair of lungs.

There were few guests in the church. Perhaps thirty at most. The happy couple stood at the altar as the vicar went through the motions. The ring was produced. There was a kiss, a couple of sighs from the congregation. These were not rich people. Not notable. They were poor workers. A stonemason and a kitchen maid. They had wished for a bright day in the little old church on the hill, but had staggered into something else entirely. The pre-nuptial bliss of heady expectation appeared to have been swept away, and the joy of their blessed union only seemed to materialise in brief flashes. The organ played, accompanying a shuffle of feet and sporadic coughs, the couple turned to make their way along the aisle, and then it happened.

Clang!Scrape. It was loud, disturbing.

Everyone froze. The old oak double doors flew open, to reveal the elderly verger, his creased black cassock hanging limp around him, his visage pale, wide-eyed, open-mouthed and momentarily speechless. The congregation gathered in a tight group behind the bride and groom wondering first what that sound had been, and then directed their communal gaze in the direction of where the verger pointed with a shaky, bony and.

It was huge. A ship’s anchor, caught up in the curvature of the Gothic arch of the church’s main portal. A proper ship’s anchor, wet, even displaying here and there tiny remnants of shiny, deep green seaweed. Although it must have weighed more than a ton, it was not on the stony floor, but up there, its huge bent iron fluke grating and jammed aloft against the door’s keystone. The vicar pushed his way forward through the gathering to face the dazed verger.

“What on earth is this, Robinson?” The Reverend’s accusatory tone suggested that this bizarre maritime intrusion might be his verger’s doing. The anchor moved slightly, its pointed fluke crunching, clanking and grating against the old stonework as if it was being pulled from above.

“I do not know, Reverend. I am at a loss … but step outside please …” The puzzled vicar followed the stunned verger out onto the path which cut through the churchyard. Behind them, the murmuring wedding party shuffled more like mourners out into the grey, wet, clinging air. The verger pointed up beyond the church door. The anchor was attached to a heavy, three inch thick hawser which stretched skywards, disappearing into the low, sinister overcast which even obscured the church’s steeple. Every few seconds the hawser snapped taut, pulling at the trapped anchor.

The groom stepped to the front of the crowd.

“I have heard that certain men in France can fly a steam-powered dirigible or a balloon, sir. Perhaps such a voyage is in progress here and their anchor has become trapped.”

The bride’s portly, red-faced father came to his new son-in-law’s side.

“No lad, no. I’ve seen balloon men in flight. In all my years in the navy, I have come to recognise a ship’s anchor when I see one. Look at the size and weight of the device! Look at the heavy rope attached - such a weight would be enough ballast to stop any balloon leaving the ground! If any ballooning men tried to even coil that rope in their basket, why, there’d be no room for humanity. This is a ship’s anchor, lad, aye, and a big ship at that.”

The chattering party, all staring upwards, now assembled itself in a wide semi-circle around the scene as the vicar walked up and down, his face a mask of frustration.

“Well whatever this is, ladies and gentlemen, we are 80 miles from the sea here, but if that anchor is not released from the archway then the fabric of our church could be damaged.” His eyes following the line of the rope in the sky, he cupped his hands to his mouth and shouted.

“Ahoy there! Ahoy above! Slacken your rope and your anchor will be freed! Call back if you can hear us!”

Everyone fell silent. From above the low, heavy cloud there came a strange rumbling, a sound as if cannon balls were rolling on a wooden deck. Then a creaking, like timbers challenged by a tidal swell. The rope snapped tight again, and with a crash a piece of masonry fell from above the church door, shattering into chunks on the ancient flagstones.

The vicar shouted again, as did other men in the party, followed by more wooden rumbling from above. The rope was taut now, the anchor’s fluke still trapped beneath the arch. Slowly, the crowd fell silent until suddenly the bride, her bouquet in one hand, pointed upward with the other, gasping;

“Look! Look! Oh, sweet Lord!”

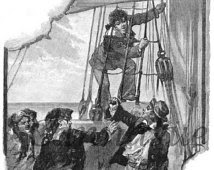

Where the rope vanished into the heavy overcast, a pair of legs appeared entwined around it. They were clad in cream canvas trousers, the feet in black leather boots. To the massed gasp of the observers, the rest of the figure shinning down the hawser came into view. He wore a waist-length navy blue moleskin jacket, a white canvas waistcoat and a black fur cap. He descended slowly, his young, pale face a mask of anxiety framed by straggly, wet ringlets of blonde hair. His livid-lipped mouth appeared to open and close like that of a fish in a pond. When he reached a height just above the church door, he paused and stared fearfully down at the circle of startled faces.

“What is the meaning of this, sailor?” said the vicar, adopting a haughty, pompous tone. But the young man’s mouth, fish-like, simply opened and closed again. He turned his face away from them and descended a little further until his boots touched the arch above the church door.

The groom, father-in-law and vicar stepped forward, staring up at the terrified youth.

“You must free this anchor immediately!” barked the vicar, “and take your balloon elsewhere! This is a house of God and this is outrageous!”

The sailor slid down further and began frantically kicking at the anchor’s shank in an attempt to free it.

“Tell your captain to slacken off!” cried the father-in-law. The youth simply stared back, his mouth opening and closing silently, wearing an expression one might expect from someone who had seen a gathering of ghosts.

The groom turned to the verger.

“Do you have any ropes here in the church?”

The verger clutched his temples.

“Yes. In the belfry, we have some there.”

“Then let’s fetch them” said the groom, “that lad needs our help!” Whilst the hapless sky sailor continued to kick and pull at the trapped anchor to no effect, the verger, the father-in-law and the groom re-appeared with a large coil of rope. The father-in-law, proving his nautical past, hastily tied a running bowline, stepped beneath the anchor and threw the loop up over the anchor’s free fluke. He paid out the line, the men in the party instinctively stepped forward and grabbed it, and all began to pull together. The anchor clanged and scraped, more small chunks of masonry fell to the ground, whilst the strange, silent sailor hung on for dear life still kicking at the anchor’s shank which had now begun to move. Sensing imminent danger, the gathered women moved several paces back and stood watching in silent awe among the churchyard’s mossy gravestones.

Suddenly, the hawser from the sky slackened off, the anchor broke free and dropped from the archway, and suspended on the end of its swinging rope just a foot above the church path, moved pendulum-like an a wide arc, narrowly missing the assembled charitable tug-of-war team with the terrified sailor clinging on, his eyes tightly closed as if expecting some disastrous impact. The anchor swung back and forth a couple of times, then became still, hovering above the path, its taut hawser a vertical sisal column, its source still obscured by the dense low cloud.

The frightened young sailor, still hanging on, now opened his eyes as the wedding party, now just a few feet below him, gathered around, regarding him in some awe.

“Who are you?” asked the vicar.

The mariner freed one hand and pointed up along the hawser. Again his mouth opened and closed, but no sound came out. Then, without warning, he lost his grip, and with an unpleasant thud, tumbled onto the church’s gravel pathway, landing spread-eagled on his back. The father-in-law charged forward, supported the stricken youth with an arm around his shoulders. His eyes, set in that pale, sad face, were deep blue and filled with tears. The father-in-law stroked the lad’s head.

“There lad, there. Where in God’s name have ye come from? Here - you’re wet through. Talk to me son - can ye talk? What’s up yonder - is she a balloon?”

The sailor’s chest heaved up and down. He shook his head. He seemed to have difficulty in breathing. When his faint voice finally broke through, it came with a gargle, as if his lungs were filled with water.

“I am drowning, sir. Truly this place and all here are marvellous. But my ship awaits, my captain is a hard man, and I cannot live here, though verily, sir, I wish I could. Take me out of the marvellous … help me lest I drown; I can breathe no more …”

The father-in-law laid the lad gently down.

“Get yonder rope free!” he shouted, pointing to the hovering anchor.

“Now, lads, step up. We must tie this poor soul to the anchor, or he will die.”

Three men held the limp sailor aloft as the father-in-law tied him securely to the anchor. As the vicar stood back and observed the suspended youth, a strange, deep wave of compassion engulfed him. The vision of the sailor secured to the anchor shocked him as it was reminiscent of the crucified Christ. The vicar fell to his knees and silently prayed as the father-in-law stood by the anchor, and in a loud voice projecting upwards yelled

“Haul away above up there - haul away before your brave salt dies his death!”

Above from the greyness came a wooden rumbling and what sounded like the thump of footsteps on timbers. The anchor suddenly lurched upwards, two feet, four feet, stop, start, stop, start, until, just before its shank pierced the dense sky, the limp sailor opened his eyes, smiled down at everyone and waved. Then the whole bizarre apparition was gone.

Later on that day, the foul wet air cleared and the sun came out. In the village inn, as the wedding party tried to enjoy their feast, they muttered in subdued tones about signs and omens. It would be, said the groom, ‘a wedding day to remember’. But when the somewhat shaken village blacksmith burst into the bar and demanded a large rum, telling the smirking landlord he had witnessed a ship, a frigate in full sail, pass by in the sky above his forge, then apart from the wedding party, the other regulars laughed out long and loud. But the vicar, the verger, the father in law, the bride and groom knew that whatever life held in store, at least the world they inhabited was, according to a spectral, drowning sailor, nothing less than marvellous.

v v v v